Am I a Developer Yet? Lessons from Cursor, Claude Code and “autonomous” building.

TL;DR:

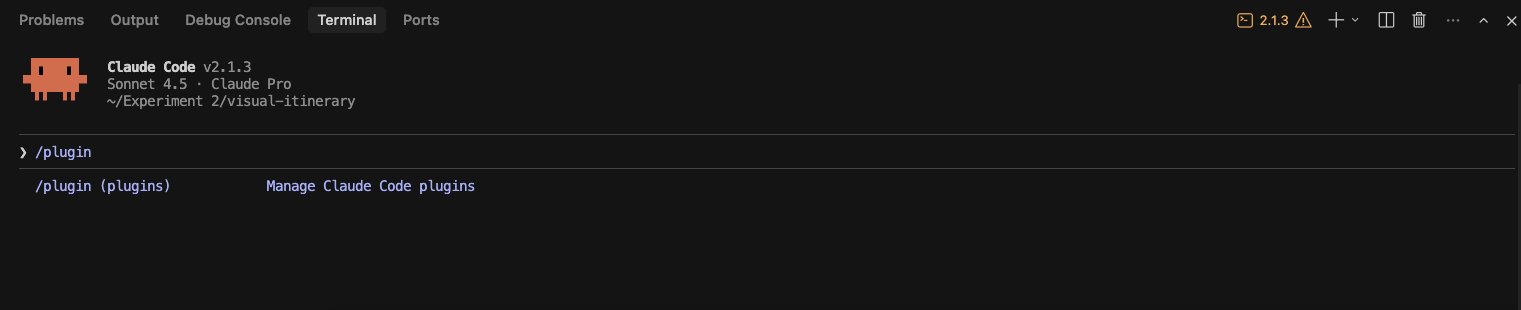

New Claude code plugins are finally good enough to change how designers think about autonomy

Automation loops break less on tech and more on human expectation

Building Trip Genie taught me why “almost working” tools will reshape how designers work and think

Early in 2025, I began experimenting with IDEs like Cursor, cautiously returning to coding after years spent in UX. In recent weeks, Claude Code’s new plugin library brought us one step closer to autonomous design and development. An engineer friend urged me to suspend disbelief and trust that the tools would eventually let designers code like pros. That advice marked a shift in how I think about my role, and how I believe many designers will work in the years ahead.

Just a few months later, I was using the OpenAI API and connecting SQL databases to ship my own conversational experiences without writing a line of code.

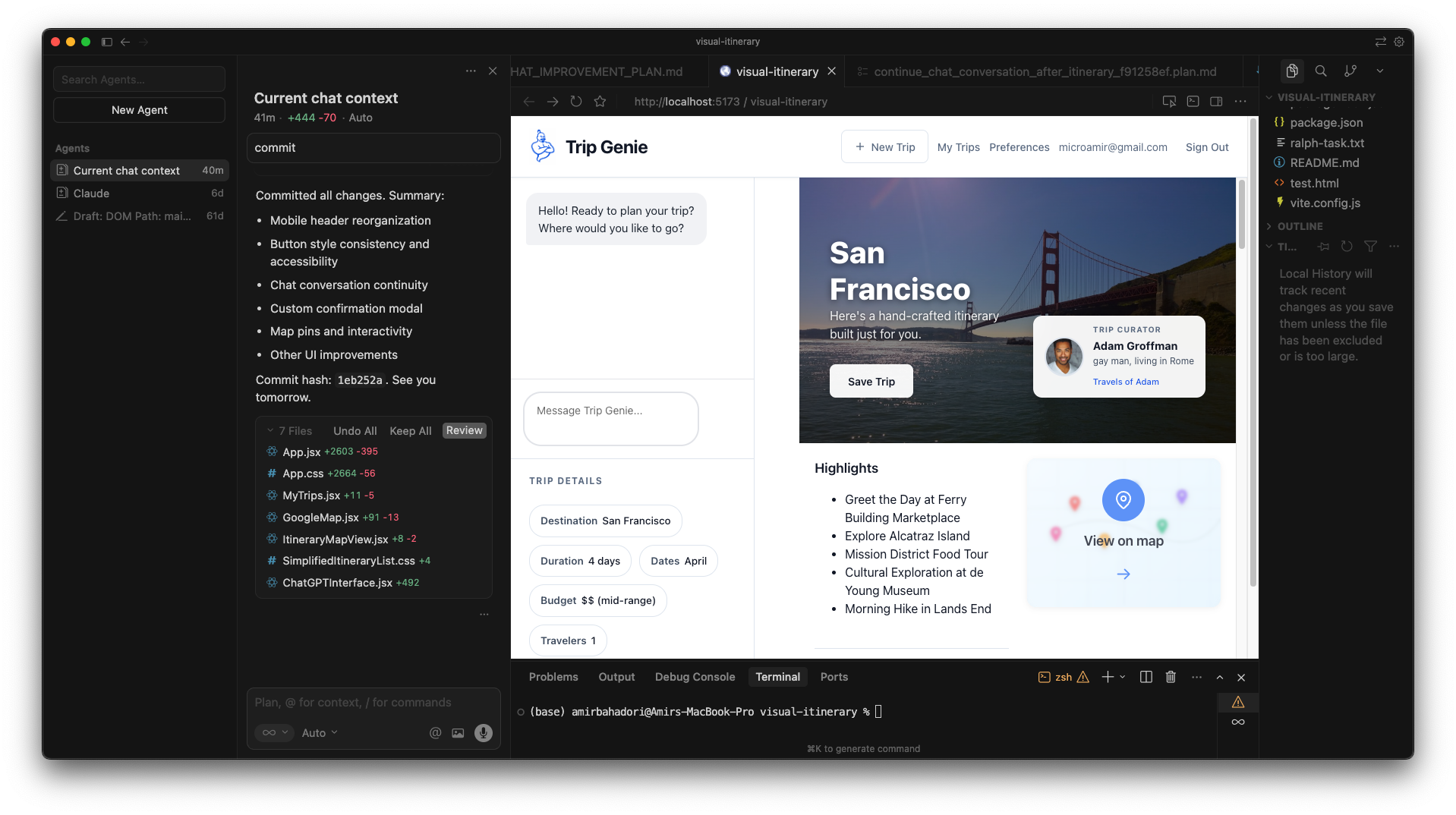

That shift gained fresh momentum when I applied this workflow to a persistent problem that kept frustrating me in ChatGPT. The result was an AI-powered trip advisor I dubbed Trip Genie, which quickly showed its potential.

I envisioned an itinerary that is both informative and visually fun!

You ask AI for an itinerary for a trip you’re planning. It gives you something great. New places and restaurants to discover. You feel a spark of excitement. Then the itinerary just dies. It lives in a chat thread, maybe gets pasted into a doc, and never evolves. There’s no continuity. No memory. No way to keep working with it like a living thing.

I kept thinking: why can’t the itinerary itself be the thing you keep talking to? Why shouldn’t it remember preferences, accept updates, and change as you go?

That question became Trip Genie.

Yes, tools like this probably already exist. But one of the strange side effects of the current AI moment is realizing you can build very specific tools for your own brain. Once you see that, it’s hard to justify using tools designed for everyone else.

So I decided to build it. Here’s what I learned.

1. Make it real as fast as possible

A year ago, getting comfortable with developer tools, without the niceties of Figma, was an uphill climb. The tools themselves were evolving quickly, and even while testing locally and going in circles with Claude, I followed a rule I’ve lived by most of my career:

Make it real as fast as possible, and you can test, learn and iterate from there. With AI that’s easier than ever, so the focus is now on the designers special sauce. Our taste, intuition and breath of experience with UX and UI patterns. And there’s no better way to expose or check the limitations and needs of the AI then by trying to build something you really, really want out there.

I described the key user tasks in the prompt, focusing on the user’s journey from point A to point B as I imagined them. I mocked up a placeholder logo, and prompted the first iterations of Trip Genie. Within minutes, the scaffolding of what I envisioned existed. The project stopped feeling like an experiment and started feeling real. The energy changed. I cared more. I pushed further.

That’s when I knew I was committed.

2. Accept that the tools are powerful and flawed at the same time

My initial plan was simple and, in hindsight, slightly flawed.

I wanted to give Claude a UX plan, hand over the work, and let it run. In my head, it looked like a mostly autonomous loop. I’d step away, come back later, and find meaningful progress waiting for me.

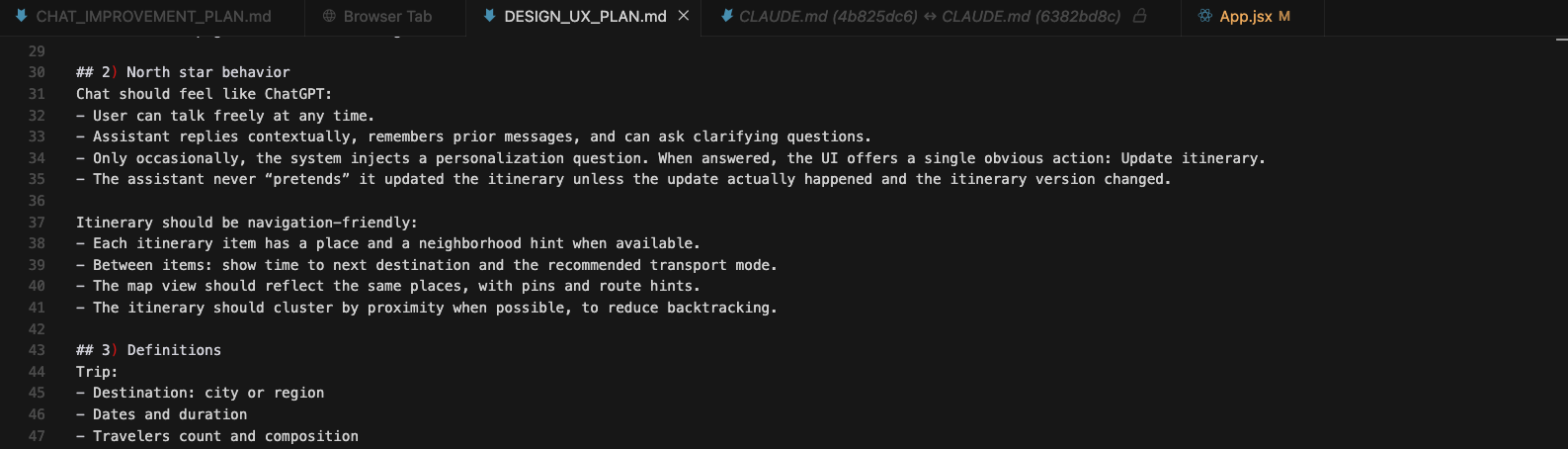

This is an .md file, think of it as your instructions for the system you can refer to in the conversation.. you can put your design north star plan in here.

In reality, Claude chat, and the more recent Claude Chrome extension, and Claude Code do work together, but their activation paths are different and not always obvious. Knowing which tool is “listening,” when, and in what context isn’t intuitive. That gap matters more than I expected.

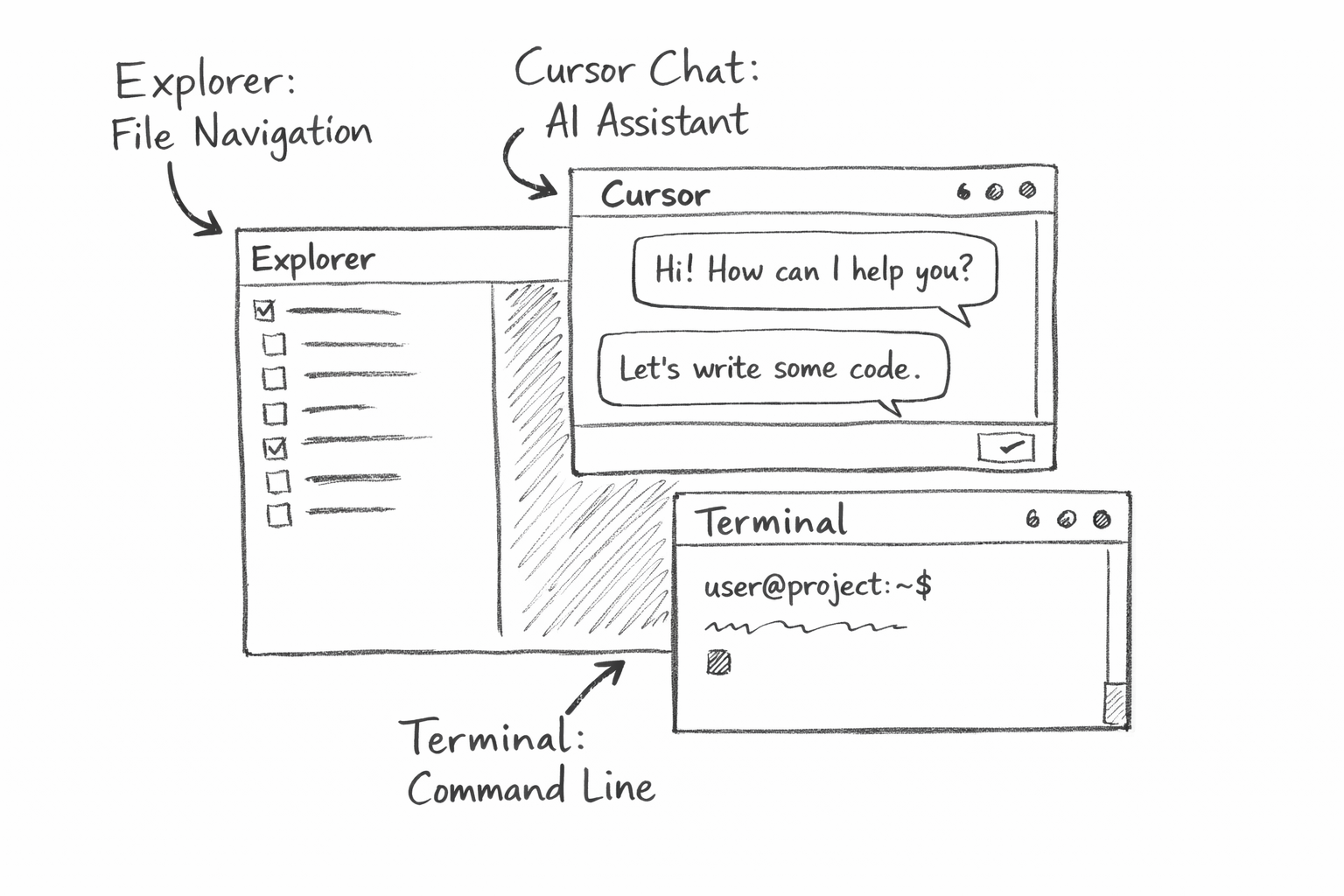

This is where Cursor is strong. The chat assistant is embedded directly in the UI, which makes everything feel askable. Stuck on a terminal command? Ask Claude. Unsure what a file does? Ask Claude. The boundary between the tool and the conversation mostly disappears.

Early on, the visual editor wasn’t there yet. You couldn’t really edit designs using tokens, grids, or structured UI primitives like you can now. I started using Cursor before those features existed, which felt a bit like learning the hard way. But that evolution is the point. Design and engineering are being pulled closer together, and Cursor is actively collapsing that gap.

Known taht led to a more important realization.

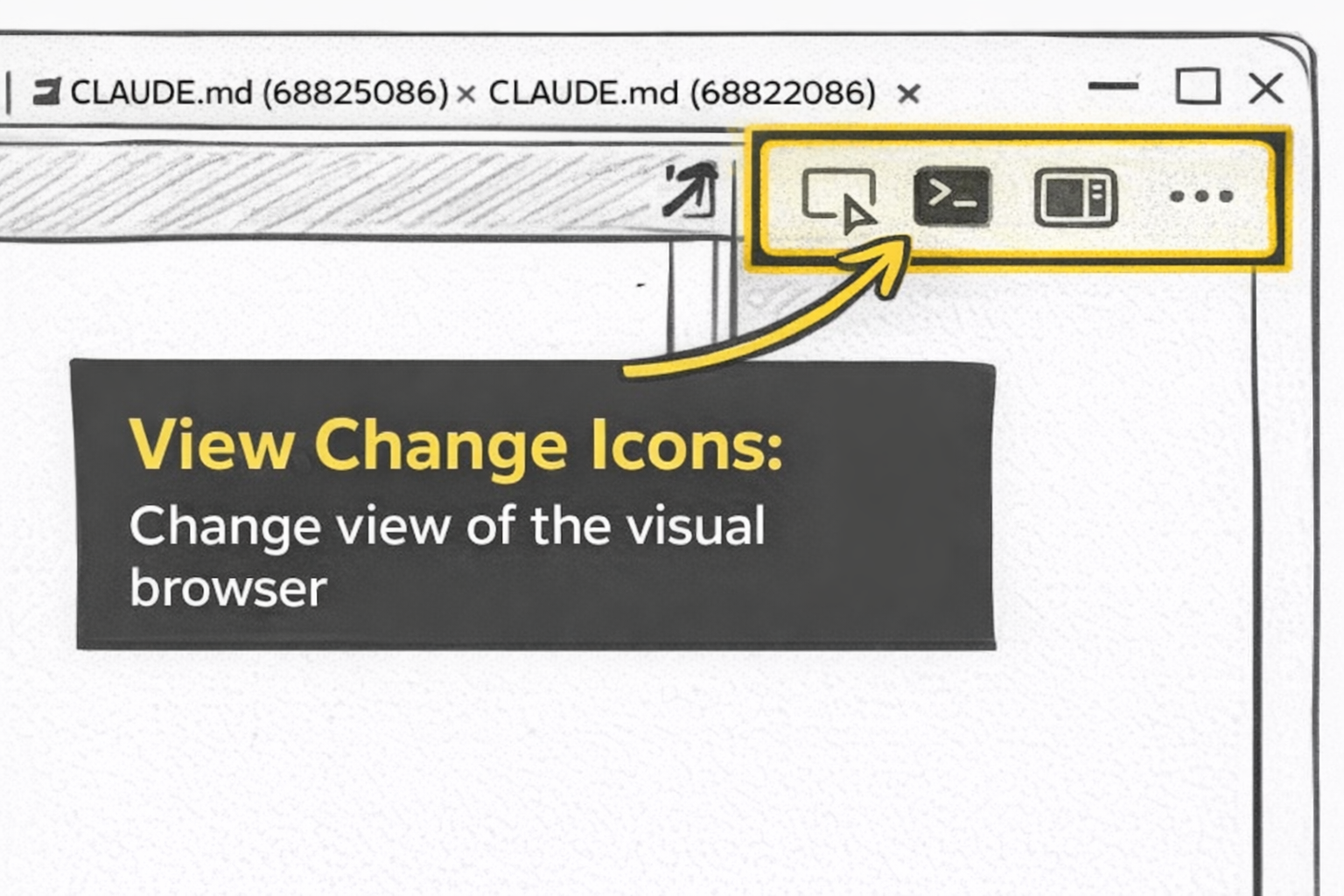

These tools aren’t built for mass consumption yet. They’re powerful under the hood, but rough at the edges. Too much responsibility still falls on the user to understand how pieces connect, when context carries over, and when it doesn’t. Good design will eventually smooth those seams. For example, Cursor still uses teeny, tiny, undisoverable icons to change the view in the visual browser. For now, the magic is real, but it still demands patience, curiosity, and a tolerance for friction.

These undiscoverable icons will change the way you design

3. When you’re stuck, rethink, research, or re‑imagine

Anthropic’s new plugin ecosystem made it possible to run longer automation loops inside Cursor, so I experimented with /ralph-wiggum:ralph-loop expecting steady, hands‑off progress. I eventually got it running, but in practice the loop kept stalling or drifting, and I’d return to a blank screen instead of momentum. It became obvious that long loops only shine when the task is stable and tightly defined, and my workflow was anything but. The ideas were still forming, the direction kept shifting, and each iteration changed what I actually wanted to build.

So I pivoted. I used Claude’s plan mode to sketch the roadmap, then moved into a phased approach using the chat and the Chrome plugin. That gave me far more control over pacing, let me fold in the unexpected ideas Claude surfaced, and helped me spot technical limits before sinking time into the wrong path. Once I stopped forcing the loop and started working in deliberate phases, the project finally moved forward.

And of course, this is just one way to work. Some folks may thrive on fully automated runs; others prefer hands-on steering. I landed somewhere in the middle, enough structure to keep things moving, enough control to shape the outcome.

4. I have to remind myself that I am the human‑in‑the‑loop

At one point, I realized I’d quietly become the message bus between systems, translating features between tools, stitching together plans, prompts, and partial executions. The overhead wasn’t thinking about the product anymore; it was managing coordination. Hours slipped by circling the same technical constraints.

The Claude Chrome plugin was a perfect example. At first, I couldn’t even tell if it was working. Cursor offered almost no feedback, so I kept firing prompts into the void, wondering whether anything was actually happening. Then, suddenly, my browser glowed, and Claude began interacting directly with my product inside the browser. Watching the system poke at the interface, run a self‑test, and respond to real state changes felt like a tiny moment of magic. A glimpse of what this whole ecosystem could become.

And yet, even with that spark, I still had to manage the loop. A simple human tweak: turning on audible notifications in Cursor’s settings, let me step away and trust the system to call me back when it needed input. That tiny adjustment shifted the whole workflow.

That’s when I stopped asking, “Why isn’t this fully autonomous?” and started asking a better question: Am I actually moving faster, or am I just managing the AI? What can I change in my setup or my expectations, to get unstuck?

Those questions helped me take back the reins, accept the system’s limits, and work with it instead of around it. Different people will want different levels of control in these hybrid workflows, some crave full automation, others prefer hands‑on steering. I’m learning to live in the middle, where the system feels alive but I still get to decide the pace.

5. What is happening under the hood isn’t always obvious

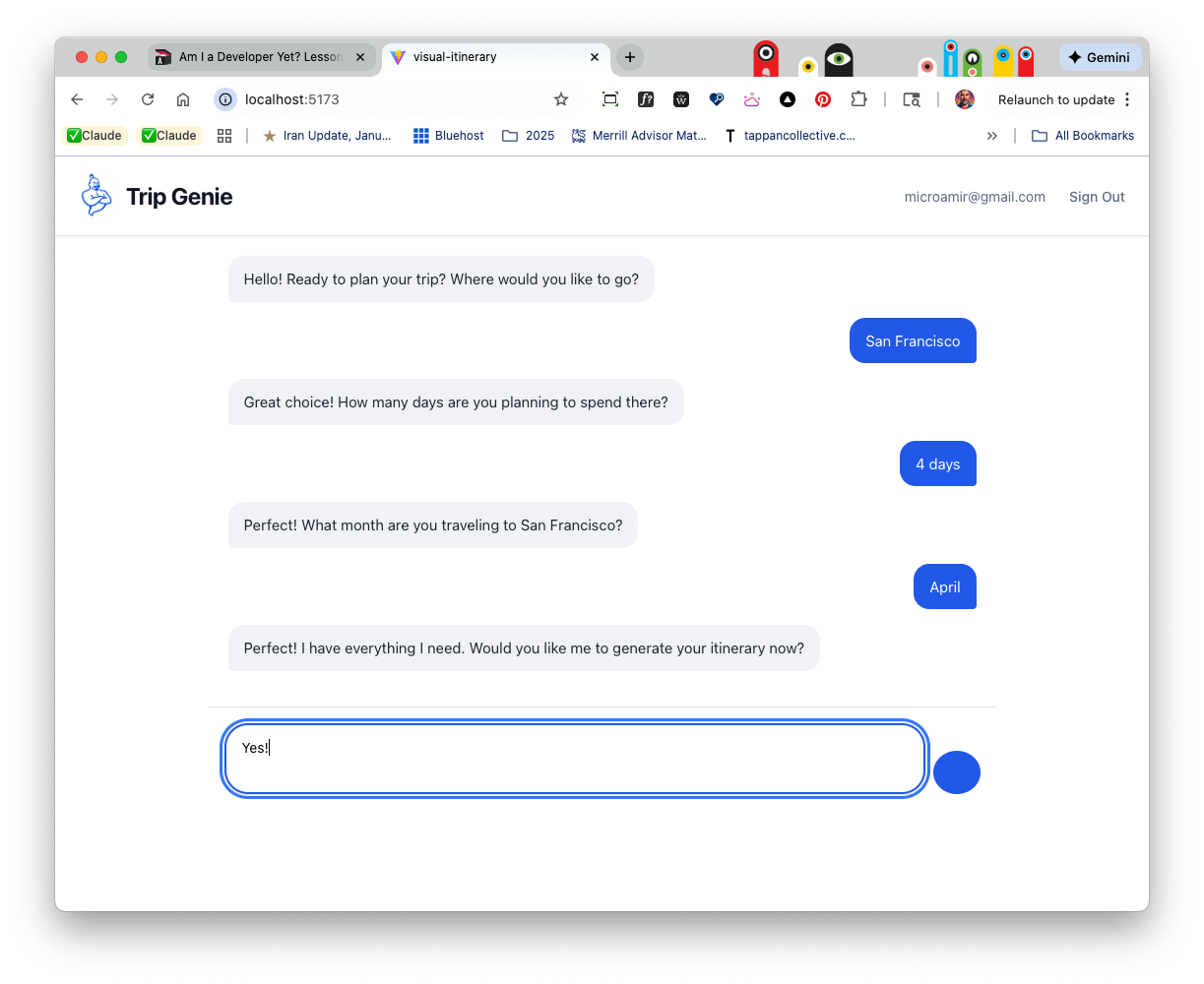

My original idea was for Trip Genie to initiate the conversation, not the user. “Where are you traveling?” it might ask. Within a narrow use case like travel planning, intent could be assumed. The system could lead.

What I didn’t fully realize was that I wasn’t building a conversation at all. I was writing a script that was being hardcoded. When I went off-script during testing, the system broke. Because I wasn’t deeply inside the code, it wasn’t always clear what was hardcoded versus what was actually connected to the system. The experience felt conversational on the surface, but underneath it was brittle.

When I routed everything through the OpenAI API, the conversation immediately felt cleaner and more fluid. But that change exposed a new problem. The conversation and the itinerary drifted apart. Data wasn’t being passed reliably, so user responses never actually impacted the revised itinerary. In that state, Claude still happily narrated success.

Once I accepted that I couldn’t always trust the narrator or tell what was actually connected to the system and what was just appearances, I redesigned the human-in-the-loop workflow to surface that distinction as early as possible.

These three panels are your new design tools

What I actually learned

This project forced me to unlearn a few assumptions I didn’t realize I was making.

Autonomy isn’t a switch you flip. It’s shaped by the human in charge. Models can reason endlessly, but action is always constrained by environment, permissions, and state. By state, I mean the underlying data. What’s saved, updated, and reflected when prompting ends.

The real bottleneck wasn’t intelligence or creativity. It was coordination. And building something real, even when it’s messy or half-working, taught me more than any amount of prompt tuning ever could.

Where Trip Genie is now

Trip Genie exists. It runs. It mostly works. It still needs better preference memory and cleaner data flow between conversation and itinerary. But it feels alive and it can be shown to actual humans for feedback, reactions and more. More importantly, I now understand where to push automation and where to step in without fighting the tools.

That understanding is the real product I walked away with.